In late September 1989, the Giants were waiting to clinch the N.L. West, playing the Dodgers in L.A. The San Francisco Chronicle’s Bruce Jenkins was just as intrigued by John Wetteland as by anything the Giants were doing, though:

If you’re familiar with Wetteland at all, you know he’s a little different. At the moment, he’s got a series of buttons lined up above his locker, each with a lively inscription. Some examples:

“I was raised by a pack of wild corn dogs.”

“Praying for the big one to hit L.A.”

“I’ve got a crate of Uzis and a case of scotch – let’s go to Disneyland.”

THERE’S A miniature chalkboard above each Dodger’s locker, just perfect for wise sayings, and Wetteland’s scribblings are a nightly attraction. “It smelled of baked plaid,” he wrote last night, explaining, “It’s like one of those cheap mystery novels. They always open up with something like, “The smoke in the room was that of a London fog.’

“The problem with some of these guys is, they can’t figure out ‘plaid’.”

Remember, Wetteland is the guy who started this whole mess Monday night.

“So what about it, John?” someone asked. “You and Martinez really showed those Giants.”

Wetteland just shrugged. “Beats painting,” he said.

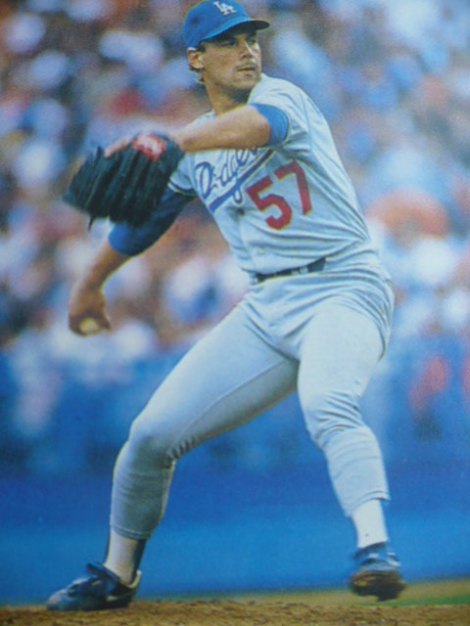

A picture of Wetteland pitching for the ’89 Dodgers:

A half-year later, in spring 1990, Wetteland was 1-4 with a 7.52 ERA. He said: “It’s like I’ve landed in a hole deep enough so that they have to pump sunlight to you. I’ve got to find a way out. This is the worst time of my career. All I can hope is after I pitch 10 years, I can look back on these two months of pure hell and know that it was worth it.

“I’m so intense, it’s been like, every time I’ve gone out there, I’ve said, ‘This is it, this is my chance.’ And I can’t do that. You can’t keep heaping emotion on top of emotion.”

The menagerie around his locker had been replaced by a single button telling the press: “Don’t presume that I will respond in a logical or rational manner.”

Five years later, as a new Yankee early in the 1995 season, the New York Times described the changes in Wetteland’s life:

John Wetteland is drinking coffee from a large mug with the words “Jesus Lives” emblazoned across it in big, black letters. He grins and nods when someone comments on the mug. His Bible is resting on a shelf in his locker and he has a personal computer at his disposal so he can retrieve morning devotionals from an on-line program and pray before the Yankees begin another day of baseball.

Something happens to Wetteland when he walks his determined walk to the mound in pursuit of a save. Something happens when he closes his Bible, shuts off his computer and picks up a baseball to chuck it 97 miles an hour in the ninth inning.

The personable player who quotes scripture, who sometimes spends two straight hours in uniform signing autographs and who invites indigent people to live in his home in Cedar Crest, N.M., becomes, in his own words, a warrior. Asked what fans should know about him, Wetteland replied, “That I’m nuts when I’m on the mound.”

“Well, I’m not nuts,” Wetteland said, seconds after having designated himself so. “It’s funny because I’m a real nice guy in everything and easy to get along with. I will serve you until I die off the field. But, on the field, something happens, something changes, man.”

John Karl Wetteland was born in San Mateo, Calif., on Aug. 21, 1966, and adopted his father’s passions for music and baseball. Ed Wetteland pitched in the minor leagues for the Cubs and is now a pianist and cabaret performer in San Francisco. A libertarian whose family lived in a one-room cabin he built in Sebastopol, Calif., Ed housed his wife and five children in a tent beside the cabin while he was constructing it, yet he made sure John had the fanciest baseball glove around. Wetteland’s parents divorced when he was 16 and he was crushed and confused. Still is.

“I guess I haven’t,” Wetteland said when asked if he had adequately dealt with his father’s remarriage. “But it’s not like I can’t stand him or anything. My dad and I have a good relationship. We had to live with it.”

Wetteland preferred that a reporter not interview his father or his mother, Dorothy Wetteland, because he “didn’t want anyone digging into my past again.” But his father told Sports Illustrated last July that his approach was to let John select his own path in life. “I emphasized the responsibility of the individual toward society,” Ed Wetteland said. “Beyond that I allowed John to find his own way. John did not grow up in a disciplined environment. I grew up in a disciplined environment, and maybe I went the other way because of it. At times we destroyed each other, as I imagine most fathers and sons do, but I love him dearly. Life is life. The head trips are going to be there.”

The head trips were there. Wetteland almost died twice around the age of 17. Once he nearly overdosed on a combination of drugs, including LSD, at a Grateful Dead concert. Another time, Wetteland was in the front seat when a drunken friend rammed his car into a telephone pole. Something happened. He trudged on. He kept playing baseball and guitar. He kept walking crooked.

Unaware of Wetteland’s occasional struggles, the Dodgers signed the 18-year-old right-hander out of Cardinal Newman High School in Santa Rosa, Calif., in 1985. He lost 10 straight games in his second minor league season, but was promoted from Class AAA Albuquerque to the Dodgers three years later and went 5-8 with a 3.77 earned run average. Jay Howell, a friend and former teammate, still called him a “lost soul.”

Wetteland’s transformation to someone who carried Bibles everywhere and read prayers in a bawdy clubhouse started because he wanted to impress Michele [his wife]. He sent her what she called “a kind and eloquent” note while she was working as an usher at a Class AA game in Shreveport, La., in 1988 and tried wooing her by feigning interest in Christianity. Slowly, his interest became legitimate. He traces his turnaround to the moment he found money. Before the 1990 season, the Dodgers offered him a $142,500 contract and Wetteland thought he had reached nirvana. He was wrong and knew it before collecting a dollar.