The Red Sox began life in Boston at Huntington Avenue Grounds, the predecessor to Fenway Park, on May 8, 1901. The next day’s Boston Globe wrote of the 12-4 win over Philadelphia, which gave the Sox a 6-5 record:

It was the birth of a major league baseball club for Boston.

Eleven thousand five hundred persons went to dedicate the new grounds on Huntington av and cheer for the members of Capt Collins’ team.

The day was an ideal one for sport and the large crowd were the essence of good nature. It was a regular holiday attendance, and the peanut man was in high glee, as he sailed his paper bags among the joyous throngs on the bleachers.

With new grounds, and practically new teams, the lovers of the sport were not too particular about the style of ball played, so long as the home team came out victorious.

The members of the new club who had gained honors in the National league were early recognized and applauded. The welcome to Napoleon Lajoie, the captain of the Athletics, and to Capt James Collins, was the most cordial.

In the crowd were clergymen, business men, professional people, ex-ballplayers, old-time fans and an army of fresh recruits and many who had not seen a game for years.

People were there from Bangor, Me, Newport, R I, and about every city between those points, including Col Osgood of Lewiston, the sincere friend of the game for 20 years, and as warm a supporter as ever.

The large crowd was handled in an admirable manner by manager Jos. Gavin.

To tally-ho coaches drove in through the center-field gate and across the field. The first contained Col Thomas F. McCarthy, the famous old ballplayer, and a party of live sports, and the second carried Charley Kelley, Dan Daley and their friends.

The crowd gathered early at the grounds, where the Boston cadet band gave an excellent concert. Small flags were distributed by Prof Chas. Green among the crowd, and the stars and stripes gave a pretty effect.

A new feature in baseball was the megaphone man, who announced the change of players and other interesting facts that the crowd were anxious to learn.

At the close of a waltz melody three Boston players in a white uniform emerged from the players’ dressing rooms and spread out for a little triangle practice. They were the first players to appear, but were not recognized by the crowd and were given but a weak sendoff.

The tallest one was slugger McLean, the six-foot-four catcher, and the others were Shreckengost and Jones. These boys will be treated with more warmth when they show their real mettle, as the Boston fan is rather slow to warm up to a new man. . . .

The game was one of the poorest ever played in this city by the visiting team. The home team hammered the weak pitching all over the field until the crowd cried to have Bernard taken out. The home team put up a good all-round article of ball.

The work of the Quakers was worth about 3 cents on the dollar. Even Lave Cross made a bad mess of things. In the outfield Geler and Hayden couldn’t judge a fly or stop a grounder.

Cy Young was in the points for the locals and held the visitors down to a few scattered hits for seven innings, when he found the game was a walkover and threw over straight ones to save that good right wing.

In the early part of the game he was serving up curves that made the ball look as small as butterfly eggs to the Quakers. Criger was doing some nice work behind the stick, and the crowd thought of that old Cleveland leader, brave Pat Tebeau.

Chick Stahl was given a round of applause when he first went up to the plate. Chick wrenched his side and retired from the game in favor of Jones in the fifth inning. The outfield was soft, and the players often lost their footing.

Hayden opened the game with a slow grounder to Collins and was thrown out at first, Geler fanned and Fultz chipped off the first safe hit. A fine throw by Criger nipped Fultz, while headed for second.

Tommy Dowd opened for Boston with a fine single to left. Hemphill bunted to Cross and the ball was fumbled. Stahl sacrificed. Then came Capt Collins with a single and Dowd scored.

Freeman drove a liner to center and thanks to Geler got in a home run. Prent was thrown out by Cross. Criger sent out up to right field, where it was muffed. As Lewis tried for second, he was thrown out.

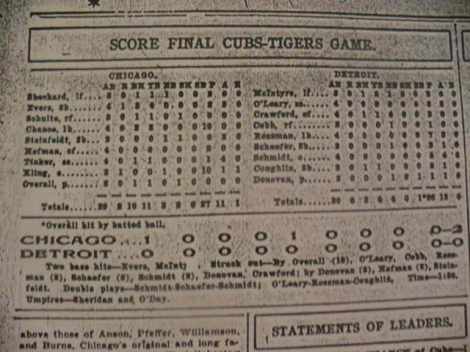

After the first inning, the description of the game action gets a little muddled, hard to follow, so let’s just proceed to the box score, in two parts:

And the headline and artwork for the debut home game, again in two parts:

The blog has already looked at the first game at Fenway and some other notable early Red Sox games, including “The Duel Between Smoky Joe Wood and Walter Johnson at Fenway Park in September 1912.”